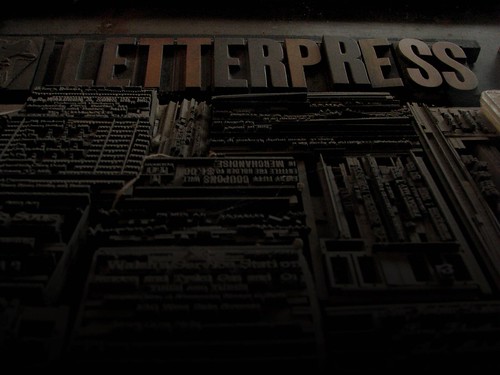

Given the recent closure of the iconic letterpress printing shop, Yee-Haw Industries, whose work adorned everything from Jack Daniels to Le Sport Sac to the movie posters for Self-Reliant Film, today's post on Kiss the Paper, a film about letterpress's decline and revival, seems especially timely.

***

Fiona Otway is a director, cinematographer, editor, producer, and media instructor whose work is influenced by her background in cultural anthropology, critical social theory, and experimental filmmaking. She has edited three Academy Award nominee films, including one of the three stories in James Longley's Iraq in Fragments, which garnered a "Best Documentary Editing" award at Sundance.

Her latest short, Kiss the Paper, is a documentary portrait of Alan Runfeldt, a man who has been a letterpress printer since age 12. Told through poetic camerawork and moody, natural lighting, the film both paints a portrait of its subject character, Alan, while also exploring the world of tactile printing--a world that stands in opposition to and is threatened by the computers and cell phones even this hardcore letterpress printer has come to adopt and rely upon.

An example of thoughtful, poignant, and self-reliant filmmaking, Kiss the Paper is a meditation on art versus profession, trade versus craft, and the ways in which analog is hanging on in a digital world.

For those readers attending Full Frame Festival in Durham, you can catch the film today!

How did you meet the subject of your film, Alan Runfeldt, and what inspired you to make a film about him?

I had been wanting to make a film about letterpress for a long time and was living in Philadelphia, where there is a lot of printing history. I started talking to folks in the letterpress community in town, asking whether they knew of any printers who had been around long enough to witness the past few decades of changing letterpress history. A few names were suggested, but to my dismay, these printers had already retired or closed their businesses and were very hard to track down.

So I started expanding my search beyond Philadelphia and when I heard that Alan Runfeldt had filled an old chicken barn with a collection of printing presses he had rescued, I knew that I wanted to talk with him. From our very first conversation, it was obvious that Alan is a man filled with incredible passion. He was very friendly and eager to share his many decades of accumulated wisdom. Soon after we chatted, I traveled to Frenchtown, NJ to visit his print shop and discovered a treasure trove of beautiful, beloved machines under his care. Since I was interested in exploring the themes of tactility and obsolescence -- both visually and through a character portrait -- Alan and his presses were the perfect subject.

Your credits on the film are producer, director, camera, and editor. Tell me about the process of making this film, which appears to be a more or less one-woman show. Were there any challenges or benefits to making the film in this way?

I had a very narrow window of time in which to make the film (between other projects), so working solo was partly a practical issue of flexibility and expediency. It’s easier to shoot a film on the fly when you don’t have to coordinate schedules and availability with a lot of people. I also simply didn’t have any budget to hire other professionals to work with me one this one. But I wasn’t completely alone; my friend Ginger Jolly came with me on one of the shoot days and was a huge help in setting up lights, recording sound, and schlepping gear -- not to mention the creative support of bouncing ideas around together. We had a lot of fun.

I have to admit, although it can be more difficult to work solo, I also really like shooting and editing my own material. I had a pretty strong vision for this piece from the very beginning, and there is a creative joy that comes with being able to shape the material in such a hands-on, start-to-finish process.

Of course, collaborating with others to make a film can be an incredible experience too. I also freelance as a shooter and editor, so I know firsthand that sometimes it just makes more sense to have a team of people creating a film together. A film can be greatly enhanced by individuals bringing their unique strengths, talents, and perspectives to the process.

In addition to this film, you've also edited a significant number of successful films, including James Longley's Iraq in Fragments, for which you won Sundance's first ever prize for "Best Documentary Editing." How do you go about the process of editing another person's film? In other words, how do you go about crafting footage into a story? What is your process of collaboration? Do you have any special processes or techniques for getting through that first assembly or rough cut?

The process of collaboration is unique to each project. As an editor, I’ve found that every director has their own working style and each project has its own creative needs.

In the beginning, my job as an editor is to really get to know the footage — its strengths, its idiosyncrasies, its potential. I’m also engaging in a rich dialogue with the director, absorbing as much information as I can about their vision for the film. Sometimes I end up doing my own additional research on the subject matter, so that I can understand the context of the story better. I might also study other films for aesthetic inspiration and use these kinds of films as a reference point for ongoing discussions with director.

As I get deeper into the edit, I am working to find a structure that will carry the story. I write outlines, start assembling scenes that I think are especially strong, build spreadsheets, make notes on index cards, and begin playing with ideas and possible approaches for a story arc. To get to the first assembly or rough cut, I’m searching for interesting resonances in the footage and in the story — the questions and themes that become more nuanced over time and make the material come alive for me. One of the aspects of editing that I love the most is that it allows me to tap into a deeply intuitive level of creativity.

Throughout the entire editing process, I’m continuing to have conversations with the director. We are constantly working to refine our vision for the movie. We’ll watch rough cuts together, make notes about what’s working and not working, and then chisel away some more. At a certain point, we’ll start showing rough cuts to a trusted circle of friends and colleagues in order to get feedback from outside the edit room. This invaluable feedback gets folded back into the editing, and the process continues in these cycles until a movie is born.

The lamentation and nostalgia that your film's subject, Alan, expresses about the decline of analog technology seems especially poignant, given this film's digital format. Did you question making this film digitally, or was that an intentional juxtaposition from the start?

KISS THE PAPER is actually shot on both super-16mm film and HD video, which was a very deliberate expressive choice from the beginning. With the recent news about Kodak’s bankruptcy, there are obvious parallels between filmmaking and letterpress printing. While KISS THE PAPER isn’t making specific commentary on the the decline of celluloid, I was very interested in the formal subtext of combining film and video in the making of the piece.

At one point, your film's subject Alan says, "Technology moves towards efficiency, but art moves towards emotion and feeling." Your cinematography, which turns heavy, oily letterpress machinery into a cinematic poetry of sorts, would seem to agree. Is this an edict that you feel accurately describes your work? How so?

I definitely have a soft spot in my heart for old technologies and tactile media, but I’m not opposed to the evolution of technology. I do, however, sometimes worry that we live in a culture that blindly worships technological progress for its own sake.

As a filmmaker, I make no apologies about working in a digital medium. In fact, the digital revolution in video is what has enabled me and others like me to have access to the tools of filmmaking in the first place. But at the same time, I want to create work that connects with people and enables people to connect with each other. So I spend a lot of time thinking about how digital technologies and digital media can either support or inhibit these goals. I often contemplate what is lost and what is gained in the fact of our increasingly digital lives and in the march towards ever-increasing technological efficiency. These are some of the questions that led me to make KISS THE PAPER.

The film premiered this January at Slamdance and has also screened at Big Sky Documentary Festival. Where else can audiences hope to catch this film?

KISS THE PAPER premiered at the Athens International Film and Video Festival in 2011. The film is still in the festival circuit, and has screened at Silverdocs, the Citizen Jane Film Festival, Red Rock Film Festival, Slamdance, Big Sky Documentary Film Festival, and Sebastopol Documentary Film Festival. The next few confirmed screenings include Full Frame Documentary Film Festival in Durham, NC, then DOXA in Vancouver BC, and at the 2012 New Hampshire Living History event in August. Additional screenings and the eventual DVD will be announced on our

.

, a 9/11-themed anthology in which I participated), and I've admired his work for some time, so in December I asked if Caveh would be interested in doing an interview for this website. My intention was to help draw attention to his film because, at the time, he was self-distributing it to theaters. Caveh agreed to the interview and, during our exchange of our emails in January, I Am A Sex Addict was picked up by IFC Films -- an exciting development. The IFC pick-up also made some

, a 9/11-themed anthology in which I participated), and I've admired his work for some time, so in December I asked if Caveh would be interested in doing an interview for this website. My intention was to help draw attention to his film because, at the time, he was self-distributing it to theaters. Caveh agreed to the interview and, during our exchange of our emails in January, I Am A Sex Addict was picked up by IFC Films -- an exciting development. The IFC pick-up also made some